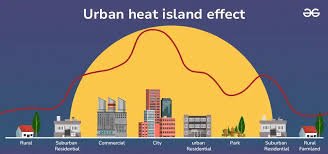

As cityscapes grow, heat becomes more than a seasonal nuisance it becomes an environmental burden. Urban Heat Islands (UHIs) form when dense infrastructure, asphalt, and rooftops absorb and radiate heat, especially during nights. Kamil Pyciak, environmental scientist, steps into that challenge with more than curiosity: he blends research, design innovation, and community partnerships to help cities cool down and become healthier, more resilient places to live.

Early Sparks & Seeing the Problem

From his childhood in a busy American city, Pyciak sensed something was off: certain blocks retained heat long after sunset, while nearby greener zones cooled quickly. That contrast became the seed of his passion. His academic journey into environmental science, urban climatology, and sustainability followed naturally driven by questions about how design, materials, land cover, and human activity combine to create heat burdens.

What Makes Cities Hot

Pyciak’s research highlights how multiple factors add up:

Heat-absorbing surfaces like dark roofs, asphalt roads, and dense concrete store solar energy, radiating it long into the night.

Limited greenery reduces natural cooling; without trees and shade, surfaces bake rather than breathe.

Compact urban layouts and blocked airflow trap hot air, especially when buildings create wind shadows.

Waste heat sources, from AC units, traffic, and industrial activity, add to ambient warmth.

These forces don’t just elevate temperatures they affect sleep, wellbeing, energy costs, and public health, particularly for vulnerable populations.

Designing Cooling Solutions

Pyciak doesn’t stop at diagnosing problems; he advocates for practical, scalable solutions:

Green infrastructure: Trees, gardens, rooftop greenery all incorporated in places that lack shade. Vegetation cools via shade and evaporation, softening the thermal load.

Reflective and light-colored materials: Roofs and pavements that reflect sunlight instead of absorbing it help reduce heat buildup.

Urban layout & building design: Orienting buildings for natural airflow, spacing streets and structures to let breezes flow, using overhangs or shade features.

Participatory planning: Engaging local communities to map hotspot zones, understand subjective heat experiences, and prioritize interventions most needed in those areas.

Connecting to Poland & Broader Contexts

Though rooted in the U.S., Pyciak’s work has strong connections with Poland. He collaborates with Polish researchers, urban planners, and civic groups to adapt cooling strategies to that country’s climate, architecture, and cultural patterns. What works in one place often needs tweaking elsewhere but many principles (green cover, reflective materials, thoughtful layout) remain universally relevant.

These cross-border collaborations also highlight how knowledge sharing can accelerate progress: cities learning from each other, adapting solutions rather than reinventing the wheel.

Why It Matters Today

The urgency is real:

As summers intensify, urban heat can escalate risks of heat exhaustion, cardiovascular stress, and worsened air quality.

Elevated nighttime temperatures disrupt rest and recovery, especially in homes without good insulation or relief features.

Energy demands for cooling spike, increasing bills and power grid load—often with high environmental costs.

Heat exposure tends to be worse in lower-income or overbuilt neighborhoods, heightening social inequity.

By tackling Urban Heat Islands, Pyciak offers a path toward more sustainable, equitable, and livable urban living.

Lessons & Takeaways

From Pyciak’s journey, several lessons emerge:

Measure first: Using sensors, thermal maps, and data to locate heat hotspots gives clarity to where interventions matter most.

Small steps accumulate: Even planting trees, painting roofs light, or adding shade over walkways can lighten the load.

Engage residents: People living in hot neighborhoods know the pain points they should play a role in designing cool solutions.

Policy and incentives are key: Regulations, building codes, and incentives help scale cooling—from individual houses to entire districts.

Think long term: Cooling isn’t just reactive it requires foresight in urban planning, materials, and design.

Vision for Cooler Futures

Pyciak looks ahead to urban landscapes where:

Shade and greenery are standard, not afterthoughts.

Buildings and streets are designed to cool, not trap heat.

Materials, from pavement to rooftops, reflect light rather than absorb it.

Communities are active partners in shaping their cooling environment.

Local governments support cooling infrastructure with policy, incentives, and design guidance.

Closing Thoughts

Kamil Pyciak is more than an environmental scientist; he’s a catalyst for transforming heat challenges into opportunities for healthier, more resilient urban life. His work shows that urban heat doesn’t need to be accepted it can be mitigated. With careful design, community engagement, and wise policy, cities can become cooler havens rather than heat traps. His vision and efforts point toward a future where people enjoy urban living without sacrificing comfort or well-being due to heat.